Two stories recently hit my feed:

The 90 year old Diane Feinstein — Senator for California — recently ceded power of her attorney to her daughter. She continues to serve as Senator.

Mitch McConnell, then 81 year old Senate Minority Leader, had a medical episode live on TV. This came only 4 months after he fell and broke several ribs.

President Joe Biden is 80. Nancy Pelosi is 82. Chuck Schumer, the Senate Majority Leader, is 72.

It certainly seems like American politicians are getting old — very, very old.

To test whether this is true, I pulled the biographies of every US Senator and Congressman from the Library of Congress. You can too here.

It turns out, yes, American politicians are objectively getting older. But there are a few interesting take-aways form the data.

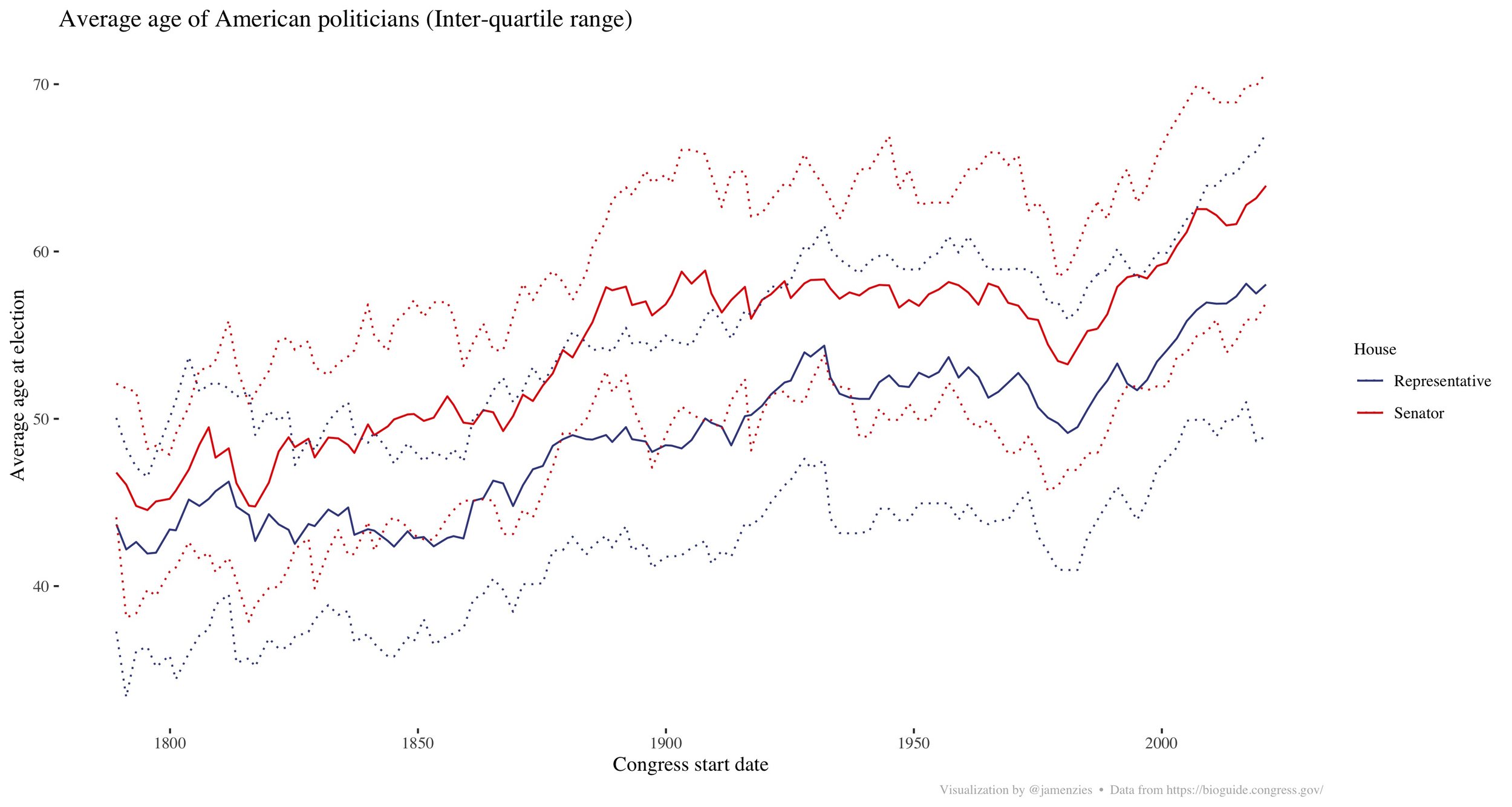

American politicians have been getting older. But it has occurred in fits and starts: In the 1800’s the average age of Senators and Congressmen was around 45. Senators saw a modest increase in average age over the next 50 years but both Congressmen and Senators saw a large increase in age after the American Civil war.

There was another burst in the 1920’s and 1930’s — but then something changed in the late 1970’s / early 1980’s. After a brief dip, both the average age of Senators and Congressmen began an inexorable increase.

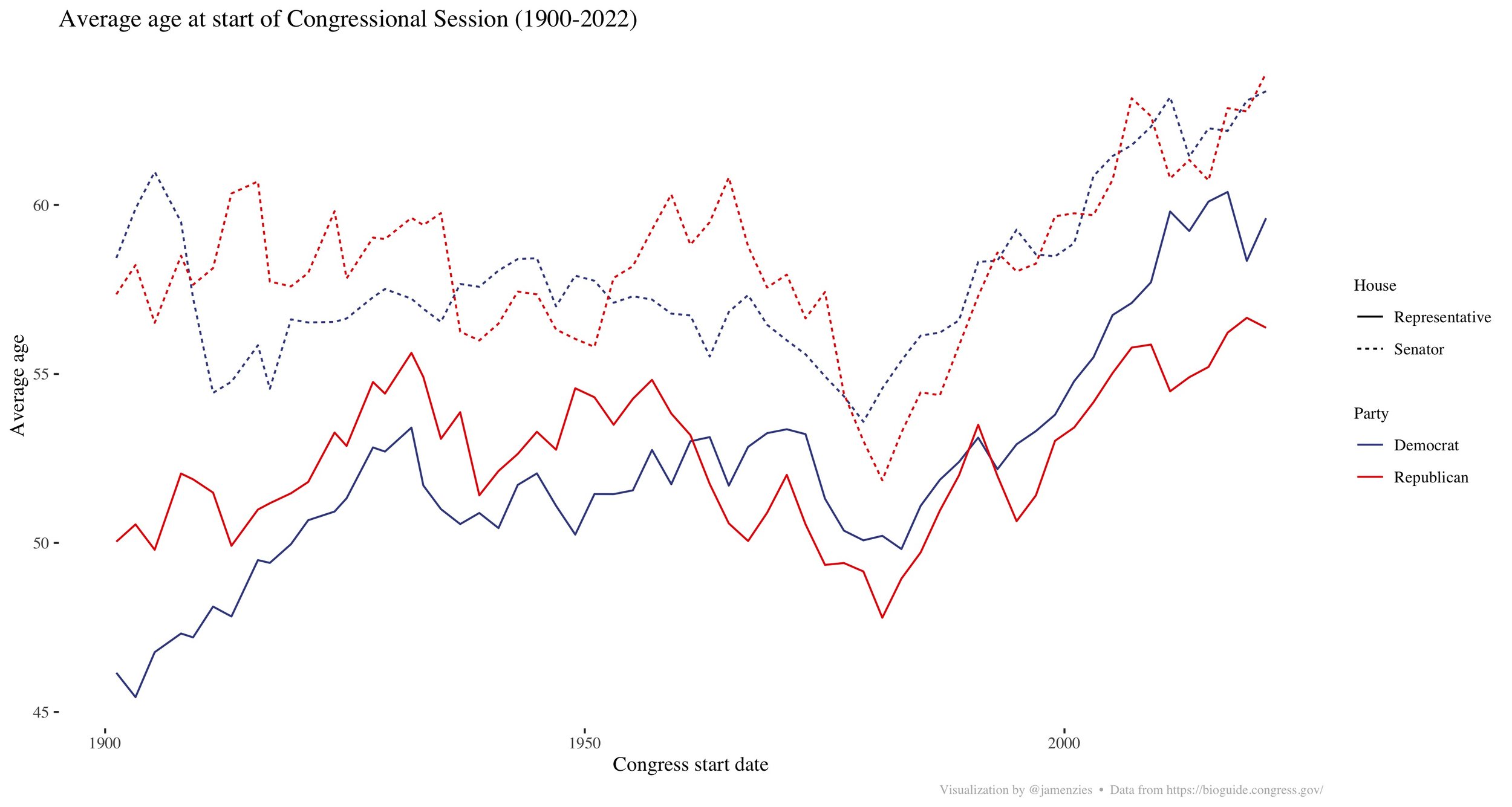

Oddly enough, this occurred for both Republicans and Democrats. But is it just because the incumbents keep winning? No.

Although new winners are (on average) younger than incumbents, the average age of new winners has increased 1980 onwards. So what do you think changed?